By Santa J. Bartholomew M.D. FAAP, FCCM

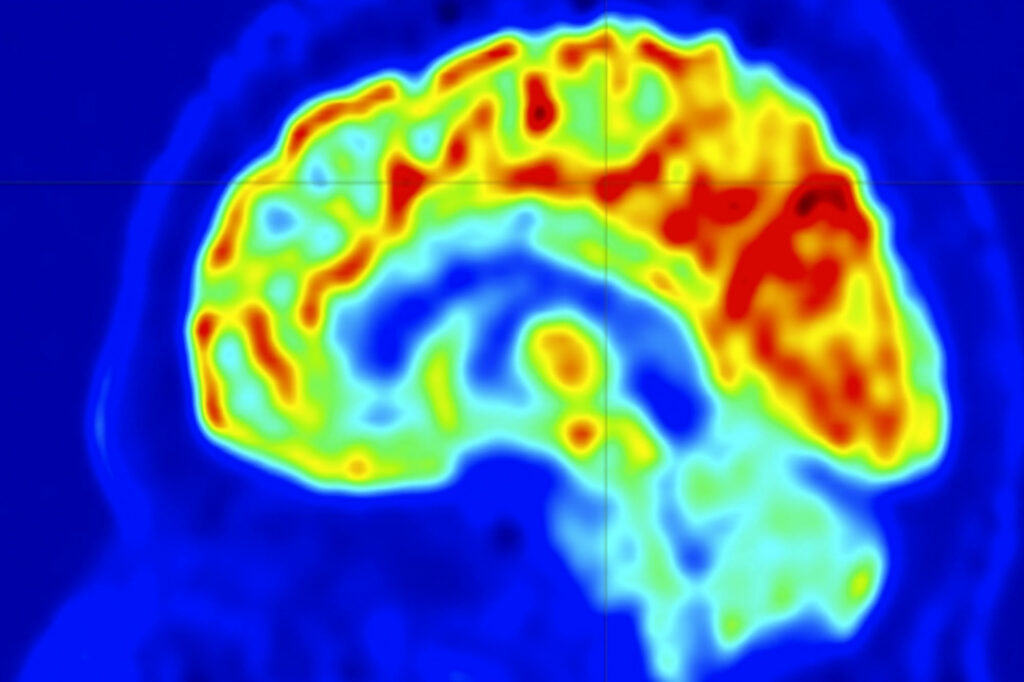

Status epilepticus (SE) is characterized by prolonged (>30 minutes) or recurrent closely associated seizures without a return to baseline. It is a common pediatric neurological emergency with an estimated incidence of 18–23 per 100,000 children per year and a mortality of 2%–7% (the range depending on the underlying etiology for the seizure). Management includes prompt administration of appropriate anti-seizure medications, identification and management of the reason for the seizure, as well as identification and management of associated systemic complications such as electrolyte disturbances, stroke, or infection. Management also includes protecting and ensuring the child is safe during the seizure period.

While the brain is electrically misfiring, it may not send the right signals for breathing well or swallowing or acid may build up from the muscles constantly twitching and this can alter how the heart functions- these things may need to be taken over by the care provider until the child has stopped seizing. That may be as simple as placing oxygen on the child or one may need to place the child on a ventilator to help with breathing and oxygen supply to the brain.

The Definition

Status epilepticus is one seizure lasting 30 minutes or more, or a series of seizures in proximity in which the child does not return to baseline in between. The incidence of SE is highest in the neonatal period and declines until approximately five years of age with a higher incidence in vulnerable populations such as those with acute or chronic neurologic conditions, like old strokes, intraventricular hemorrhage, old asphyxial injuries, and the like. Despite the cause of seizures there is an urgency to abate seizures in children before they cause secondary injury to the brain. As such the American Academy of Neurology as recommended a series of closely timed actions in abating seizure and discovering the cause.

Status epilepticus should be identified and treated as quickly as possible to avoid brain injury from prolonged seizures.

The Neurocritical Care Society guideline recommends:

- a finger-stick glucose in the initial two minutes as well as a serum glucose

- complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, blood gas, calcium, magnesium, and anti-seizure medication levels drawn in the initial five minutes

These rapidly correctable causes of status epilepticus should be identified and treated as quickly as possible, including hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia, and hypomagnesemia to avoid brain injury from prolonged seizures.

Additional diagnostic testing including lumbar puncture, neuroimaging, and other blood work (liver function tests, coagulation panel, serum or urine drug screen, and inborn errors of metabolism screen), which are recommended to be performed in the initial hour depending on age and circumstance of seizure.

Management Goals

Consideration should also be given to performing continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring. The Neurocritical Care Society’s guideline stipulates that EEG monitoring should be initiated 15–60 min after seizure onset to evaluate for non-convulsive status epilepticus for patients who are not returning to baseline within 10 min of convulsive seizure cessation or within 60 min for patients in whom ongoing seizures are suspected.

The principal management goal is the cessation of both clinical and electrographic seizure activity as quickly as possible to avoid secondary injury.

Once seizures have been stopped then the focus changes to identifying the cause of the seizure. In children, infectious reasons are the biggest culprit for status epilepticus accounting for up to 12% of patients. Infections include acute bacterial meningitis; acute viral meningitis or encephalitis; and subacute viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic meningitis. The most common infectious etiologies vary by age, acuity, whether the patient is immunocompromised, use of steroids or other immunosuppression, recent travel, animal exposures, season, and associated signs and symptoms. Initiation of appropriate antibiotics after the performance of an LP or as soon as possible if the LP is going to be delayed is a priority.

Clinicians should suspect an autoimmune encephalitis in the presence of an otherwise unexplained cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis or elevated protein, evidence of inflammation of limbic structures on MRI, recent-onset systemic symptoms concerning malignancy, or when status epilepticus occurs as part of a subacute neurologic degenerative disorder and further investigation is warranted. And finally, space-occupying lesions such as tumors and stroke.

Management includes treatment of the cause, which is out of the scope of this document, and treatment of seizure defined below.

Immediate Management

- Non-invasive airway protection and gas exchange with head positioning

- Intubation, if needed

- Monitoring O2 saturation, blood pressure heart rate, temperature

- Finger stick blood glucose

- Peripheral IV access

- Medical and Neurologic Examination

- Labs: BMP, Magnesium, Phosphate, CBC, LFT, Coagulation Tests, ABG, anticonvulsant levels

- Emergent Initial Therapy (given immediately)

- Consider whether out-of-hospital benzodiazepines have been administered when considering how many doses to administer.

- With IV Lorazepam 0.1mg/kg IV (max 4mg) may repeat if seizures persist

- Without IV Diazapam 2-5 years 0.5mg/kg; 6-11 years 0.3mg/kg; ≥ 12 years 0.2g/kg (max 20mg) Midazolam IM if 13-40kg, then 5mg; if > 40kg, then 10mg. Intranasal 0.2mg/kg. Buccal 0.5mg/kg

Urgent Management

- Additional diagnostic testing as indicated: LP, CT, MRI, toxicology labs, inborn errors of metabolism.

- Consider EEG monitoring (evaluate for psychogenetic status epilepticus or persisting EEG-only seizures.

- Neurologic Consultation

Urgent Control Therapy

- Phenytoin 20mg/kg IV (may give another 10mg/kg if needed) may cause arrhythmia, hypotension, purple glove syndrome, OR

- Fosphenytoin 20PE/kg IV (may be given another 10PE/kg if needed), OR

- Consider phenobarbitol, valproate sodium, or levetiracetam

- If < 2 years, consider pyridoxine 100mg IV push

*PE = phenytoin equivalents

Refractory Status Epilepticus

Administer another Urgent Control anticonvulsant or proceed to a pharmacologic coma.

- Levetiracetam 20-60mg/kg IV

- Valproate Sodium 20-40mg/kg IV – contraindicated if liver disease, thrombocytopenia, or possible metabolic disease

- Phenobarbitol 20-40mg/kg IV – may cause respiratory depression and hypotension

Pharmacologic Coma Medications

- Midazolam 0.2mg/kg bolus (max 10mg) and then initiate infusion at 0.1mg/kg/hour – Titrate up as needed

- Pentobarbital 5mg/kg bolus and then initiate infusion at 0.5mg/kg/hour – Titrate up as needed

- Other options – Isoflurane

Pharmacologic Coma Management

Titrate to either seizure suppression or burst suppression based on EEG monitoring Continue Pharmacologic coma for 24-48 hours Modify anti-seizure medications so additional seizure coverage is in place for infusion wean Continue diagnostic testing and implementation of etiology-directed therapy

Add-On Options

- Medications: phenytoin, phenobarbitol, levetiracetam, valproate sodium, topiramate, lacosamide, ketamine, pyridoxine

- Other: epilepsy surgery, ketogenic diet, vagus nerve stimulator, immunomodulation, hypothermia, electroconvulsive therapy

Key Points

- Seizures lasting more than 30 mins are an emergency in children and can cause acid build-up, breathing issues, and lead to brain injury.

- Seizures can make the parts of the brain that control breathing and blood pressure malfunction and careful attention needs to be given to avoiding low oxygen saturations and low blood pressure as well as low blood sugar – these can all injure a seizing brain and should be avoided.

- Muscle twitching and electrical seizures use a great deal of energy and low glucoses should be treated urgently to avoid secondary brain injury.

- Underlying reasons for seizures should be quickly identified and treated.

Photo source: https://depositphotos.com