By Santa J. Bartholomew M.D. FAAP, FCCM

See Corresponding Case Study: Shaken Baby Syndrome

Shaken baby syndrome (SBS) is one form of abusive head trauma (AHT). It is a severe form of physical child abuse resulting from the violent shaking of an infant by the chest, shoulders, arms, or legs. SBS may result from either shaking alone or from shaking with impact. Babies, newborn to one year, are at the most significant risk of injury from shaking. The incidence in the first year of life is 13-40 per 100,000 children per year in the United States. Research indicates that there are likely more children who suffer from shaking incidents who are not brought in for care and are minimally injured.

Most infants who have suffered from SBS present with significant, deteriorating neurological signs, including stupor, unconsciousness, or coma. They will often have apnea or abnormal breathing patterns. Presentation typically requires immediate respiratory support, including bag-valve-mask ventilation followed by intubation and connection to a ventilator. Children who have suffered this traumatic injury will usually have significant seizure activity. Less severe injuries or those brought immediately to medical care will usually be irritable, crying, vomiting, and having brief periods of apnea. Some have anemia which is generally recognized as being associated with bleeding.

Most infants who have suffered from SBS present with significant, deteriorating neurological signs, including stupor, unconsciousness, or coma.

The most common history given is an abrupt onset of symptoms with no explanation or an explanation that does not fit the level of trauma. An example would be a baby who fell off a couch or a changing table or bumped their head while crawling.

Studies have repeatedly shown that abusive head trauma vs. accidental head trauma have a much greater degree of neurological impairment and are much more critically injured than those who are unintentionally injured. They are more likely to have seizures, need ventilatory support, and have long-term brain injury. This is because the damage usually includes a subdural hematoma. Subdural hematomas are of varying degrees of severity and cause symptoms quickly.

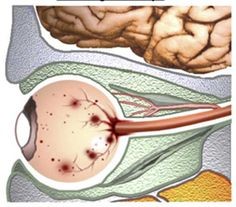

Retinal hemorrhages are found in an average of 80% of children with SBS. They are much more significant than those in children with accidental trauma. Retinal hemorrhages in a child with AHT are often too numerous to count. They are typically found widely through both retinas within multiple layers. They may be accompanied by retinoschisis, a tearing of the retinal layers. The severity of retinal hemorrhages often correlates with the severity of the brain injury.

Aside from the characteristic presentation of the child, timing is an essential variable in determining when a traumatic injury may have occurred. An infant’s environment often includes multiple caregivers who may all be suspected of having committed abuse. Pinpointing the timing may lead to identifying the perpetrator. Numerous studies have reiterated that an otherwise healthy child who has been shaken and has the most severe injuries, including those that die, will decline rapidly. Children with more moderate injuries may deteriorate slowly and have post-traumatic seizures as the intracranial bleed expands. It has been shown that children who initially present with normal or an almost-normal neurological exam rarely have significant findings on CT or MRI but remain asymptomatic.

Injury biomechanics is a sub-discipline of biomechanical engineering. A biomechanical engineer seeks to describe the forces and motions associated with the cause of injuries in the case of all injuries but may help enormously with those related to abusive trauma. Appropriate characterization of injury patterns and the associated mechanism is vital in determining the story’s validity regarding the injury. All data that can help in understanding the mechanism of pediatric injury is critical when evaluating a suspicious case for abuse.

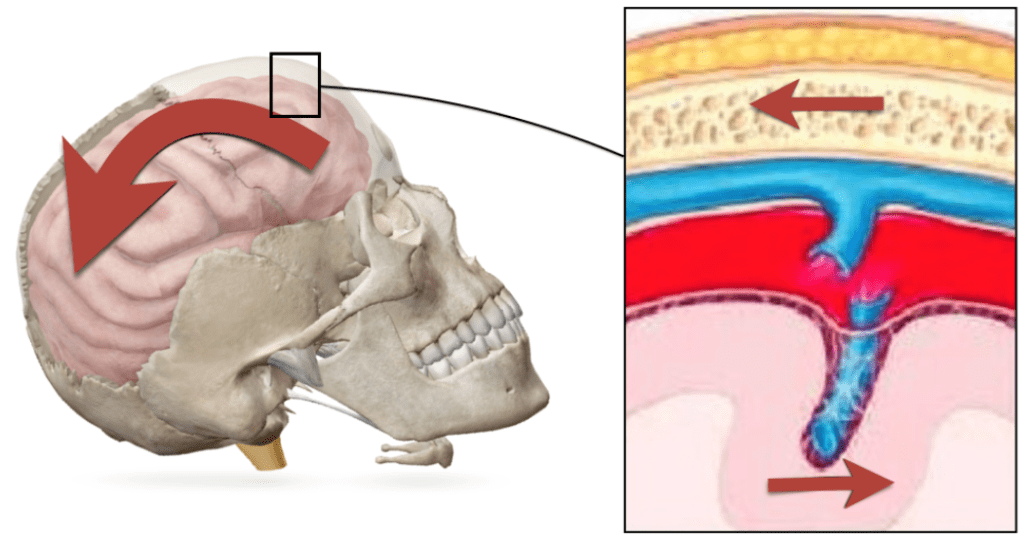

“The triad,” which consists of retinal hemorrhaging, subdural hemorrhaging, and encephalopathy, results from excessive levels of rotational head acceleration. In the case shaking, this refers to the head moving back and forth on the neck between flexion and extension. This movement is similar to vigorous nodding of the head up and down or to a whiplash. Rotational, or angular acceleration of the head, can occur during rapid movement of the torso while the head’s slowness due to size, causes it to lag. During rotational acceleration of the skull, shearing strain will develop within the contents of the skull. This shearing strain can cause a similar motion of the bridging veans attached to the dura, which can overwhelm the strength of the veins and result in rupture and bleeding.

Images depict the shearing strain developed within the skull and the resulting rupture of a bridging vein.

Thus, when an infant presents with retinal hemorrhaging, subdural hemorrhaging, and encephalopathy, the literature consistently concludes one thing; that the cause of these injuries is abusive shaking. Also, pulling on the retinas and orbital injury sustained during the repetitive acceleration-deceleration mechanism causes retinal hemorrhaging. Factors such as hypoxia, anemia, and intracranial pressure may add to the appearance of retinal hemorrhages but do not cause such retinopathy.

Rib fractures are produced by direct blows to the chest or compression of the chest while holding the infant to shake them. Young children’s ribs are flexible and difficult to fracture, so a rib fracture without a history of severe trauma, such as a motor vehicle crash or fall from a significant height, is strongly suggestive of child abuse. In one review, rib fractures in an infant with intracranial injury had a positive predictive value of 73% for abusive head trauma.

Many studies in the child abuse literature have reported that children with abusive head trauma have worse outcomes than those with accidental head trauma. Mortality from AHT averages about 19%. Significant neurological impairment is found in about 50% of those who survive. In one more specific study, 5% were vegetative, 34% were severely disabled, 25% were moderately disabled, and only 13% had good outcomes. Disabilities include various degrees of paralysis, cranial nerve impairment, seizure disorders, blindness, microcephaly, intellectual impairment, and severe behavioral disorders. Children with previous medical or developmental disabilities have worse outcomes. Other predictors of poor outcomes are repeated abuse, low socioeconomic status, low GCS on arrival to emergency care, occurrence and duration of coma and need for resuscitation.

Much research has been done since abusive head trauma was first described in 1972. Most of the literature has maintained the accuracy of the “triad” that described this type of abuse. The specificity of bleeding in the brain, encephalopathy, and retinal hemorrhages differentiates inflicted injury from other head injuries. Recent data from autopsies also supports the likelihood that cervical injuries may cause the apnea accompanying AHT.

References:

Adamsbaum C, Morel B, Ducot B, Antoni G, Rey-Salmon C. (2014) Dating the abusive head trauma episode and perpetrator statements: key points for imaging. Pediatric Radiology. Dec;44 Suppl 4:S578-88. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-014-3171-1. PMID: 25501730.

Bechtel K, Stoessel K, Leventhal JM, et al. (2004) Characteristics that distinguish accidental from abusive injury in hospitalized young children with head trauma. Pediatrics. Jul;114(1):165-168. DOI: 10.1542/peds.114.1.165. PMID: 15231923.

Caffey J. (1972) On the Theory and Practice of Shaking Infants: Its Potential Residual Effects of Permanent Brain Damage and Mental Retardation. Am J Dis Child. 124(2):161–169.

Chevignard, M. P., & Lind, K. (2014). Long-term outcome of abusive head trauma. Pediatric radiology, 44 Suppl 4, S548–S558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-014-3169-8

Duhaime, A. C., Gennarelli, T. A., Thibault, L. E., Bruce, D. A., Margulies, S. S., & Wiser, R. (1987). The shaken baby syndrome. A clinical, pathological, and biomechanical study. Journal of neurosurgery, 66(3), 409–415.

Kocher, M. S., & Kasser, J. R. (2000). Orthopaedic aspects of child abuse. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 8(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.5435/00124635-200001000-00002

Levin, A, Christian, C., (2010) Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect, Section on Ophthalmology; The Eye Examination in the Evaluation of Child Abuse. Pediatrics August; 126 (2): 376–380. 10.1542/peds.2010-1397

Maguire, S., Pickerd, N., Farewell, D., Mann, M., Tempest, V., & Kemp, A. M. (2009). Which clinical features distinguish inflicted from non-inflicted brain injury? A systematic review. Archives of disease in childhood, 94(11), 860–867. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2008.150110