By Santa J. Bartholomew M.D. FAAP, FCCM

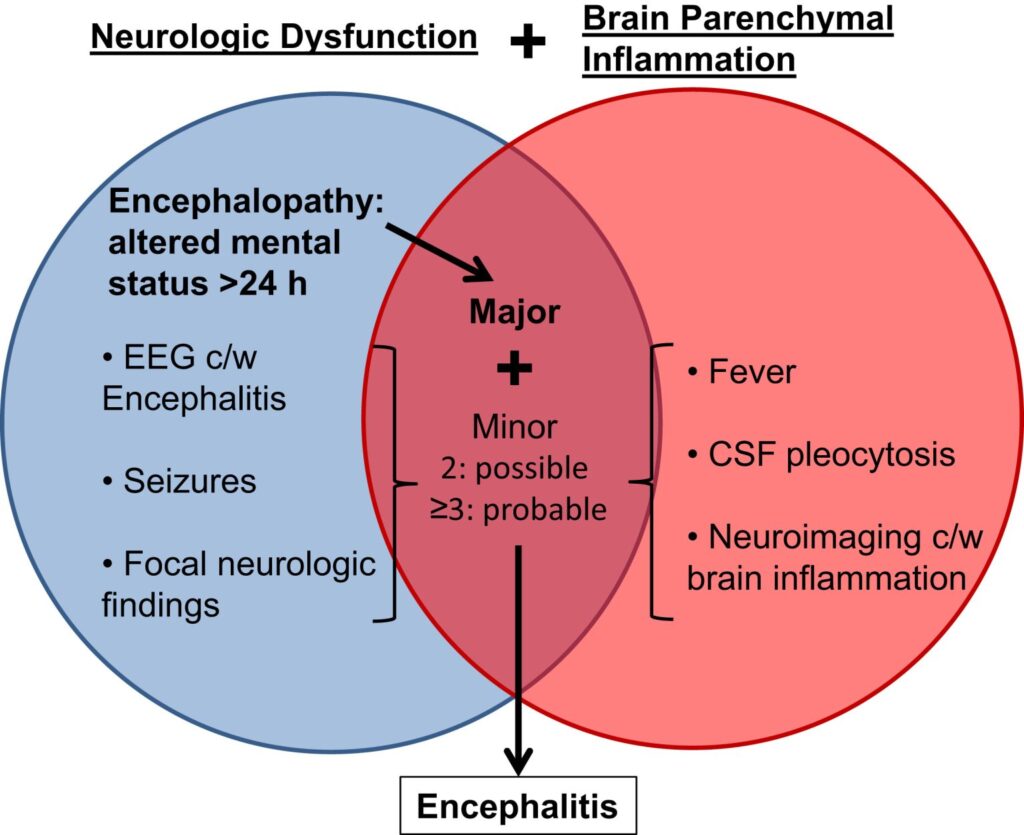

Pediatric Encephalitis is an altered mental status for more than 24 hours that is accompanied by two or more symptoms/findings that are concerning for inflammation of the brain parenchyma. The brain parenchyma is the tissue responsible for specific functions of the brain. The incidence of pediatric encephalitis is unclear, due to multiple etiologies and inconsistent definitions of encephalitis. Recent reports do indicate that cases of pediatric encephalitis may be increasing due to increased recognition of autoimmune etiologies and use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to describe abnormalities in the brain parenchyma. Up to 30% of cases of pediatric encephalitis have an undiagnosed etiology.

How Does Encephalitis Happen?

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain. This can be caused by an infection or an autoimmune cause. The inflammation is the body’s immune system reacting to the infection or invasion. The inflammation causes the brain’s tissues to become swollen. The infection can get into the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF).

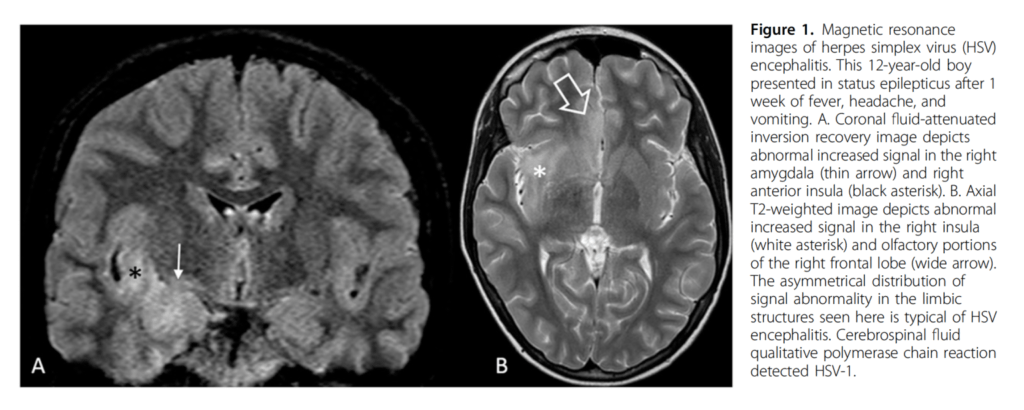

In the past, infectious agents accounted for most of the etiologies for encephalitis. Before the use of vaccinations, measles, mumps, varicella and polio were among the top causes for encephalitis. With the introduction of vaccines, other viral etiologies such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) and enterovirus (EV) have risen to the top of etiologies for infectious encephalitis in pediatrics.

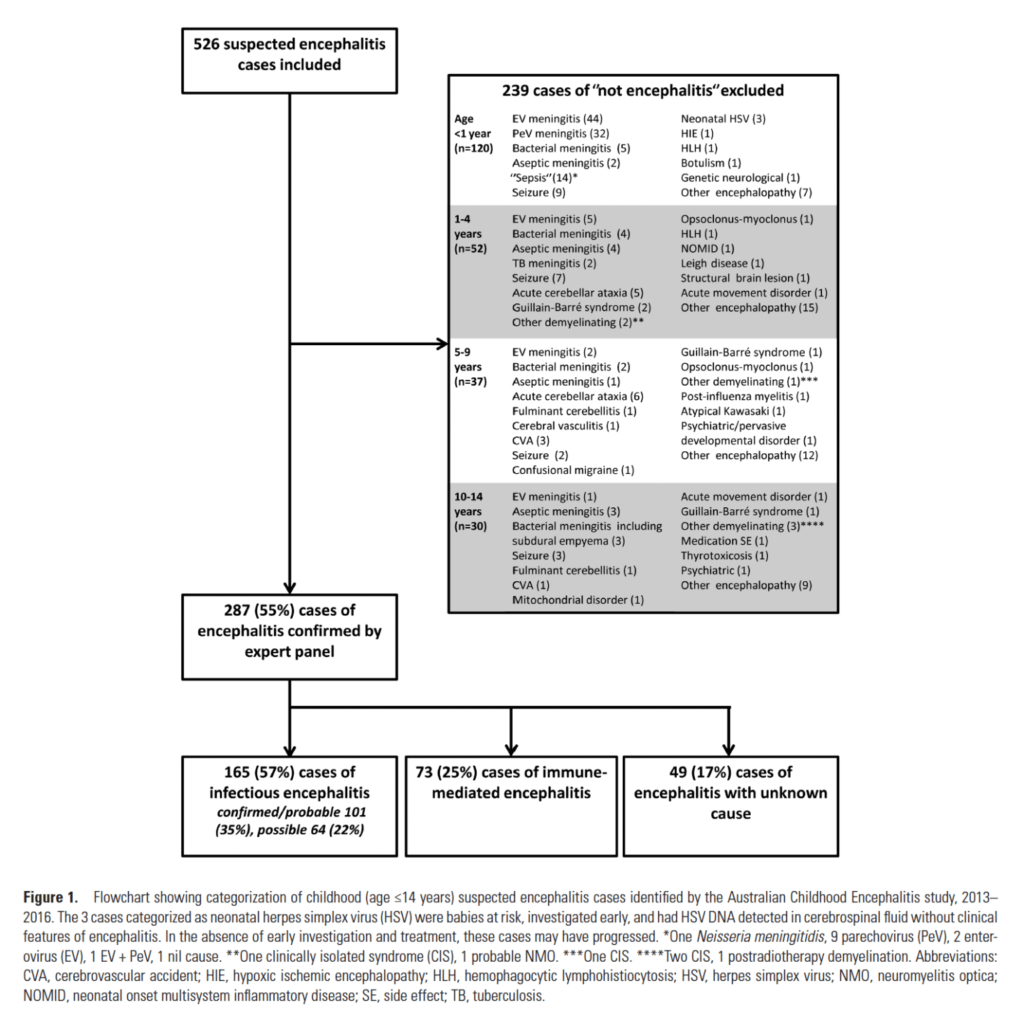

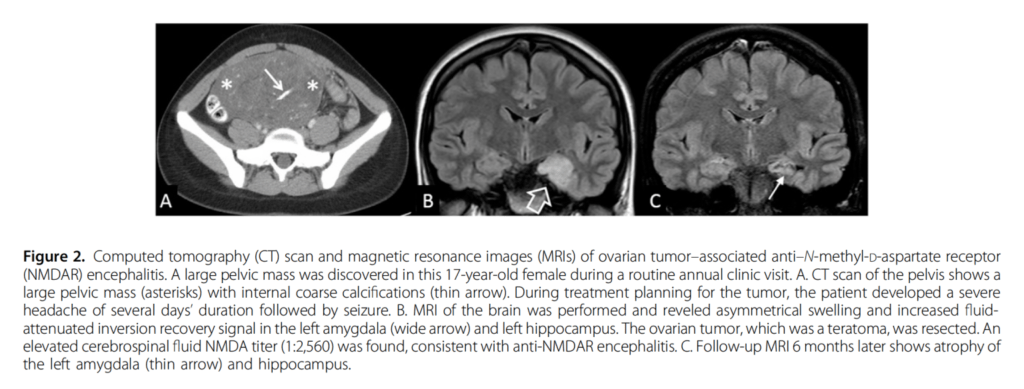

In autoimmune encephalitis, the body’s immune system attacks the brain causing inflammation. The number of cases of autoimmune encephalitis are beginning to outnumber those of viral encephalitis, with the incidence of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis exceeding the rate for a single viral etiology for pediatric encephalitis.

Table 1: Flowchart showing categorization of childhood (age ≤14 years) suspected encephalitis cases identified by the australian childhood encephalitis study, 2013-2016.

Causes

- Herpes Simplex Virus: Most common cause of pediatric encephalitis. Estimated incidence 3 to 30 cases per 100,000 live births. Serious morbidity and mortality. Transmitted intrauterine, perinatal, and postnatal

- Enterovirus: Among top causes of pediatric encephalitis

- West Nile Virus: Most common arbovirus in North America (virus spread to people by the bite of an infected arthropod/insect such as mosquitoes and ticks). <4% of cases involve children <18 years old. Transmitted by culex mosquito and therefore, mostly seen in summer

- La Crosse Virus: Second most common arbovirus in North America. 88% of all encephalitis due to La Crosse virus occurs in children <18 years of age. Most cases in Appalachian and Midwestern region of US. Usually seen in late spring through early fall. Transmitted via infected Aedes mosquito

- Zika Virus: Can cause microcephaly (small head and abnormal brain development) in infants. Transmission via infected Aedes mosquito. Seen in summer and early fall.

- Bacteria: Streptococcus pneumoniae, haemophilus influenzae serotype b, Neisseria meningitidis, Listeria monocytogenes, mycoplasma

- Autoimmune diseases

Symptoms

Symptoms may be similar for infectious and autoimmune encephalitis. A consensus statement provided by the International Encephalitis Consortium outlines diagnostic criteria for possible and confirmed encephalitis. Per this consensus statement, a requirement for encephalitis is altered mental status for >24 hours without an alternative diagnosis, and 2 or more of the additional clinical features mentioned below:

- Fever: >100°F (>38°C) within 72 hours

- Seizures: New onset or different than pre-existing seizure history

- New focal neurologic findings

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis (white blood cell count > 5/µL

- Abnormal neuroimaging findings consistent with encephalitis and/or abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG) reading consistent with encephalitis

Encephalitis may initially present with flu like symptoms. History of the illness and other physical exam findings are pertinent.

Clinical Features

- Fever (67%-80%)- More common in Viral Encephalitis

- Seizure (33%-78%)

- Headache (43%)

- Weakness or pyramidal signs (36%-78%)

- Agitation (34%)

- Decreased consciousness (47%)

- Autoimmune Encephalitis: More chronic findings with delayed diagnosis up to several weeks

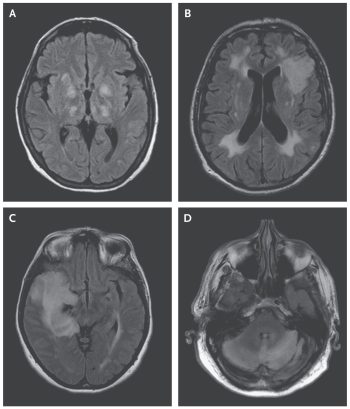

Image: MRI Patterns in Patients with Acute Viral Encephalitis

Source: New England Journal of Medicine

How Do We Diagnose Encephalitis?

- Level of suspicion based on history, signs and symptoms, epidemiologic risk factors, recent travel, recreational, occupational exposures, insect or animal contact, seasonality, mood/behavior or personality change resembling acute psychosis

- Herpes Simplex Virus: HSV is the most common cause of pediatric encephalitis and should be suspected in any child with concern of encephalitis. Ophthalmologic exam and conjunctival HSV culture to evaluate for eye involvement

- Lab Studies: CBC with differential, CMP, HSV serum PCR, Enterovirus serum PCR

- Lumbar Puncture/CSF Studies: Cell count, Protein, Glucose, Gram-stain and bacterial culture, HSV PCR, Enterovirus PCR. If patient is not improving, Autoimmune panel, Meningoencephalitis multiplex PCR panel, CSF immunoglobulin M to look for specific arboviruses such as West Nile virus and La Crosse virus, Extra CSF to freeze for additional testing (Obtain opening pressure with lumbar puncture. If there is concern for increased intracranial pressure, always obtain a head CT prior to performing a lumbar puncture

- NeuroImaging:

- MRI with and without contrast. First-line imaging test for pediatric patients with suspected intracranial infection.

- Dedicated Epilepsy Protocol MRI with and without IV contrast for suspicion of autoimmune encephalitis

- Computed Tomography (CT): Head CT without IV contrast is first line imaging in pediatric patients presenting with acute mental status change as this can quickly and accurately exclude neurosurgical emergencies

- Abdominal/Pelvic Ultrasound: Anti-NMDAR encephalitis has ha an association with ovarian teratomas. US may allow resection of the tumor to alleviate the encephalitis

- EEG: Controversial. Most patients with encephalitis will have an abnormal EEG. Recommend consultation with Pediatric Neurology

“Encephalitis in Previously Healthy Children.” Pediatrics in Review, vol. 42, no. 2, Feb 2021, pp. 68–77.

Treatment

- HSV is the leading cause of severe encephalitis and is associated with poor outcomes. Acyclovir should be initiated on all patients with suspected encephalitis until HSV is ruled out

- Empirical antibacterial antibiotics, while awaiting culture results, focused primarily on coverage for Streptococcus pneumoniae, haemophilus influenzae serotype b, Neisseria meningitidis, Listeria monocytogenes, Mycoplasma

- Corticosteroids – more commonly used for viral encephalitis such as varicella zoster and HSV if concern for swelling in the brain

- Immunomodulators (help to “calm” the immune system) – Corticosteroids, IVIG (decreases the overall burden of the offending autoantibody), Plasma exchange (potentially removes the disease causing antibodies), Rituximab

- Always evaluate for and treat any underlying disease process

Prognosis

- Highly variable. Dependent on etiologic agent/cause

- Meta-analysis examining outcomes in patients with infectious encephalitis: 42% incomplete recovery, 6.7% severe sequelae, 17.5% decrease in intelligence quotient

- HSV encephalitis: Up to 64% experience late effects such as developmental delay, neuropsychological dysfunction, and focal motor deficits

- Autoimmune encephalitis: ~ 1/3 demonstrate full recovery, 1/3 partial recovery, 1/3 with limited recovery and severe deficits

- Use of immunotherapy in autoimmune encephalitis correlates with improved outcomes

References:

Messacar, K. (2017). Encephalitis in US Children. Infectious Disease Clinics, 32(1).

Up-to Date: 2021: Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection: Clinical features and diagnosis