By Santa J. Bartholomew M.D. FAAP, FCCM

See Corresponding Journal Article: Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PARDS)

Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Tracheal Injury in a Patient Requiring Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Following Cement Aspiration: A Case Report. Böhrer, Madeleine MD, FRCPC1; Long, Cai MD2; Thompson, Adrienne MD, FRCPC, DABR3; Veroukis, Stasa MD, FRCPC4; Khaira, Gurpreet MD, FRCPC1 Critical Care Explorations 5(9):p e0969, September 2023.

A previously healthy 6-year-old boy presented to Emergency Medical Services (EMS) after falling into a cement mixing truck that contained Portland cement powder and water. He was conscious when removed and was decontaminated with water at home. On EMS arrival, he required oral suctioning and supplemental oxygen. His respiratory status deteriorated necessitating endotracheal intubation by the air medical crew approximately two and a half hours post-incident.

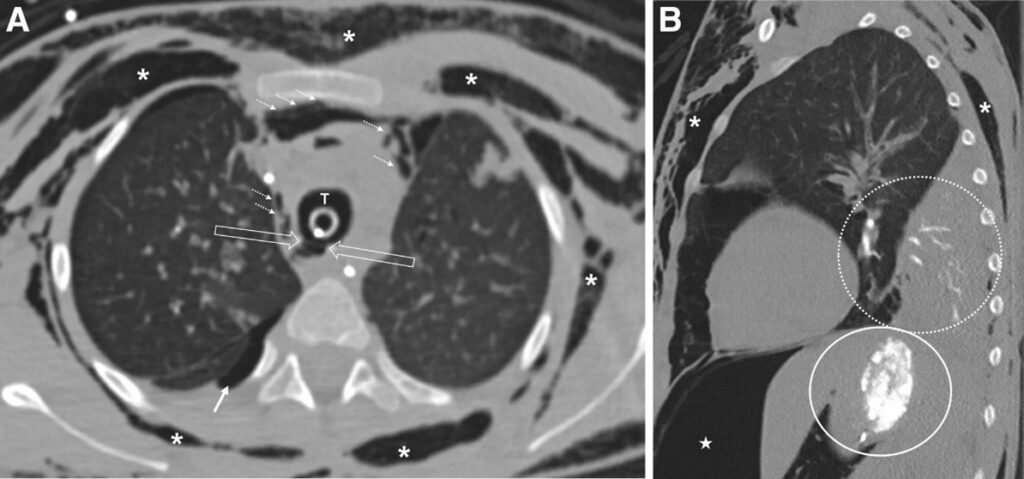

En route with the transport team, and on arrival to the tertiary care hospital, saturations of 84–90% were only sustainable with hand-bagging (Peak inspiratory Pressure of 30, positive end-expiratory pressure of 10, rate of 20–30, Fio2 100%). He had developed extensive crepitus and air leak during transport, as is evidenced by his chest radiograph on arrival at the tertiary care hospital.

As a result, he was immediately placed on high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) in the PICU. The presence of crepitus on clinical examination and pneumomediastinum before HFOV initiation and on CT post-HFOV initiation raised the suspicion of tracheal injury. Due to the patient’s respiratory instability, further imaging and a flexible bronchoscopy were not immediately feasible.

Day 3 of admission CT showed caustic tracheal injury, cement casts within airways with associated collapse, as well as cement in the stomach The patient met PALICC criteria for severe PARDS with an Oxygenation Index of 20 and bilateral cement infiltrates with collapse on CT chest (before venoarterial [VA]-ECMO) (8). Precannulation arterial blood gas showed a pH of 7.21, Pao2 of 90, Paco2 of 75, and lactate of 0.5.

Due to an inability to wean support, the value of rigid bronchoscopy was raised—ideally with ECMO backup. The patient was electively cannulated onto peripheral VA-ECMO via the neck before transport to the ECMO center. Of note, extensive subcutaneous emphysema obstructed views on transthoracic echocardiogram, making venovenous (VV)-ECMO cannulation unfeasible. Transesophageal echocardiogram posed the risk of esophageal perforation due to potential alkali burns and was contraindicated.

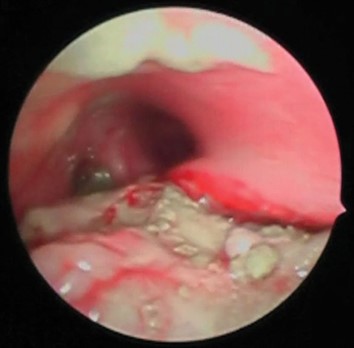

Initial bedside bronchoscopy, at the ECMO center, revealed a posterior tracheal defect and a large amount of cement debris in the airway. A total of three bronchoscopies with washout were performed to remove the amount of cement found, yielding satisfactory results

Ventilation was minimized to reduce airway pressure and allow healing of the tracheal defect while on ECMO support (a routine practice for patients on ECMO cannulated for ARDS). An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy did not reveal any mucosal defects. Cement slurry present in the stomach was managed with repeat irrigation and suctioning.

The patient was converted to VV-ECMO on day 4 of ECMO support (post-admission day 10). He was decannulated from ECMO on day 16 of ECMO support (post-admission day 22) and was ultimately extubated 41 days post-admission to low-flow nasal cannula support. The patient was discharged home, with no apparent neurologic injury, on post-admission day 62.