By Santa J. Bartholomew M.D. FAAP, FCCM & Betsy Kastak, DNP, RN, C-PNP

See Corresponding Journal Article: Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy

It was a hot summer day, and a young mother was outside with her three children, ages 2, 5, and 8 years old. They were enjoying a day of swimming and eating ice cream. The dogs started barking and the doorbell rang. The mother told the 8-year-old to watch her siblings and she would be right back, she needed to see who was at the door. After signing for a package and waiting on the package for what seemed forever, the mother returned outside. She immediately noticed the two-year-old was missing and ran to the pool where she found her youngest daughter unresponsive at the bottom of the pool. Mom pulled her from the pool, called 911 and started CPR. EMS arrived taking over CPR.

In the Emergency Department, the medical team was able to restart her heart. The child had a breathing tube placed and was taken for a head CT. She was transferred to the Pediatric Critical Care Unit (PICU).

In the PICU, the patient suffered with low oxygen levels as far down as 80% despite the mechanical ventilator and the highest amount of oxygen that the team could deliver. The child’s blood pressure was unstable requiring epinephrine to help stabilize it. Chest x-ray demonstrated pulmonary edema bilateral. The patient was then noted to have rhythmic twitching of her right arm and right leg with elevated heart rate and blood pressure thought to be seizures and was started on anti-epileptics (anti-seizure medication). The EEG demonstrated seizures for several hours despite aggressive treatment. Seizures were resolved eventually with several different anti-epileptic medications.

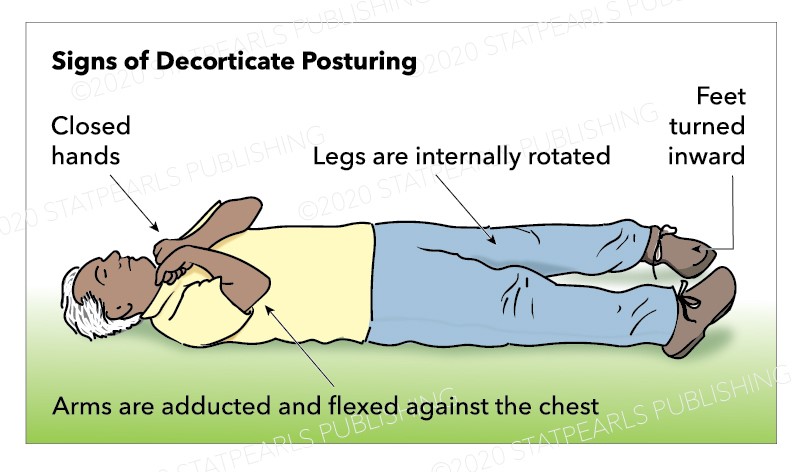

Over the next three days, the CXR improved, vent settings were weaned, and the patient was extubated to nasal cannula. Her vital signs improved allowing the epinephrine infusion to be discontinued. The EEG demonstrated no additional seizure activity. Despite her stable vital signs and respiratory effort, her neurological exam remained concerning with no spontaneous movement except for occasional decorticate posturing.

Discussion

Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE) is the sequelae of a combination of hypoxia (lack of oxygen) and ischemia (lack of blood flow) to the brain.

Common causes of HIE include cardiac arrest, prolonged seizures, asphyxia, drowning, infectious and metabolic encephalopathy, and prolonged low cardiac output states. Common causes of HIE in infants include asphyxia at birth (perinatal asphyxia) due to complications with or at delivery, infections causing meningitis and/or encephalitis, asphyxia from co-sleeping, and trauma. In older children, HIE is more often related to drowning and asphyxiation. These all cause decreased or inadequate blood flow and oxygen to the brain.

The prognosis of HIE varies and is determined by the degree of injury. An infant or young child with mild HIE may, with time, have a near full or full recovery. With moderate to severe HIE, recovery to a normal neurological state is less likely. With moderate to severe HIE, patients may require a tracheostomy/ventilator to support respiratory efforts, may be unable to eat by mouth, and may have profound disabilities requiring around the clock nursing care. Some will not survive.

Diagnosis

An important history of the event is vital to support the diagnosis of HIE. History, in combination with clinical exam and imaging helps confirm the diagnosis of HIE.

Treatment

In the acute phase, the goal is to maintain adequate blood pressure, control seizures, maintain adequate oxygen saturations/ support respiratory efforts, treat/manage infection and metabolic derangements. Despite these efforts, if the brain sustained a prolonged period of inadequate blood flow and oxygen prior to treatment, or is refractory to treatment, the injury to the brain may be severe. This applies to neonates and the pediatric population.

Therapeutic temperature management has been controversial in the treatment of HIE. In the neonatal population, it is the standard of care to provide therapeutic hypothermia for infants born at or greater than 36 weeks gestation who have moderate-severe HIE.

In the pediatric population, there is ongoing research to determine the role this plays in neurological outcomes. Currently, evidence does not support the use of moderate hypothermia (32-33 degrees C) as treatment in the pediatric population. Temperature control is vital as fever has been associated with worse neurological outcomes.