By Santa J. Bartholomew M.D. FAAP, FCCM

See Corresponding Case Study: Procedural Sedation

Diagnostic and minor procedures in children occurring outside the operating suite have increased dramatically in the last 2 decades. As a consequence, there has been an increased need for analgesia and sedation in all manner of places: physician offices, imaging centers, emergency departments, ambulatory surgery centers and inpatient settings outside of the traditional operating suite. There has also been an explosion in the types of providers providing sedation: pediatric hospitalists, pediatric critical care physicians and pediatric hospitalists. With this change it has become imperative that guidelines and policies be created to provide analgesia and sedation to children in these non-operative settings.

Given the increasing complexity of procedural sedation the Academy of Pediatrics has issued guidelines for the types of sedation and credentials of care providers to try to ameliorate the serious risks associated with sedation in children. Most adverse outcomes during sedation come from the lack of appropriate monitoring and therefore the lack of rapid diagnosis when the child is slipping from one phase of sedation to another that may alter their breathing patterns, hypoxemia, apnea or issues with hemodynamics. The other portion of sedation that can lead to adverse events lies in choosing the correct child for the appropriate sedation.

The Academy of Pediatrics has issued guidelines for the types of sedation and the credentials of the care providers to try and ameliorate the serious risks associated with sedation in children.

Pre-procedure assessment:

Who is appropriate for minimal, moderate and deep sedation? Typically, children that are ASA 1 and 2 are considered appropriate candidates for out of the OR minimal, moderate and deep sedation. These are children with no chronic disease or mild chronic disease and who have had no serious medical issues.

Children with special needs, anatomic airway issues (such as Pfeiffer’s syndrome or Treacher-Collins children), moderate or severe tonsillar hypertrophy, sleep apnea, morbid obesity should receive sedation or anesthesia by a sub specialist in anesthesia.

Pre- procedure preparation:

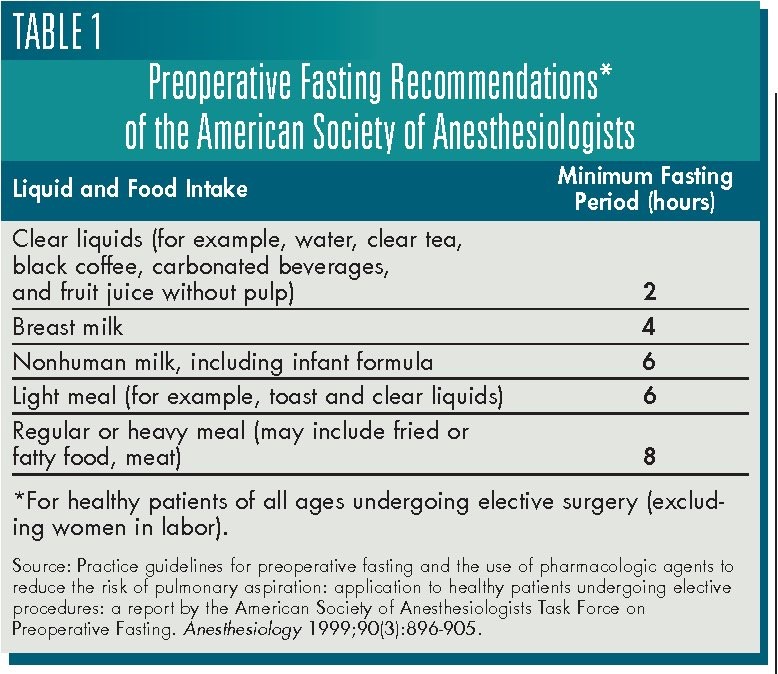

1. NPO:

NPO guidelines are to be followed for elective sedation cases.

In emergency situations the sedation physician can weigh the risks of sedation on a presumed full stomach against the benefits of sedation and earlier treatment.

The most onerous of risks are pulmonary aspiration and pneumonia.

2. Equipment and Personnel: In all sites performing sedation there should be adequate monitoring and rescue equipment. The Academy of Pediatrics has provided guidance about equipment and personnel that is attached to the end of this article. The Society for Pediatric

3. Anesthesia Checklists: Anesthesia provides emergency checklists for a myriad of emergency situations that should be available in all sedation arenas: https://pedsanesthesia.org/checklists/

a. Essential equipment:

i. Cardiovascular monitoring

ii. Pulse oximetry

iii. Carbon dioxide monitoring: capnography

b. Rescue Equipment:

i. Emergency Cart: with age and size appropriate equipment: oral and nasal airways, LMA’s, laryngoscope blades, ETT, face masks, blood pressure cuffs, IV catheters.

ii. Rescue drugs in case of airway or cardiac emergency

iii. Reversal agents.

c. Personnel:

i. All practitioners should be PALS trained or advanced airway skills.

ii. There should be a person separate from the proceduralist who monitors the patient at all times

iii. There should be others available in case of emergencies.

4. Documentation: Pre, Intra and Post procedure documentation are essential and each necessary for different reasons.

a. Pre-procedure: Is a health evaluation (is the child safe for sedation outside the OR?)

i. It documents baseline status.

ii. Determines risk factors that may impact sedation plan.

iii. Identifies medications and herbals the child may take that will interfere with sedation.

iv. Assesses the airway and risks associated with small jaw, large tongue, neck instability, snoring and like issues.

v. Review of all systems to find organ function that may alter the child’s response to sedation.

vi. Past medical history that can give clues to previous anesthesia issues or medical problems that may impact sedation.

b. Intra-procedure:

i. A time out with parents in the room and all providers should ALWAYS be performed to ensure that the right patient is in the room for the correct procedure.

ii. Once sedation has begun vitals and assessments should be done and documented every 5 minutes during the entirety of the drug infusion process.

iii. All adverse events should be documented: need for bag -valve-mask, airway interaction.

c. Post-procedure documentation:

i. Patients need to be recovered in an area where there is appropriate equipment and personnel.

ii. Vitals should be performed for 10-15 minutes, and monitoring continued until the patient is ready for discharge.

iii. Discharge needs to occur after the patient returns to baseline.

Sedation is very helpful for many procedures in children that are painful and anxiety-provoking. But sedation is dangerous if unprepared, it should not be undertaken without appropriate equipment for children, personnel trained to care for children and a space dedicated to recover children that is also appropriate equipped. Many remember a series of deaths in dentists offices two decades ago when Versed first became available , in each of these cases these children were poorly or not monitored at all and there were no rescue personnel when the child had problems breathing.